Comment on

Sanchez, M.A. ; Gil, A. y Simón, J.L. (2017): Las rocas de falla del cabalgamiento de Daroca (sector central de la Cordillera Ibérica): Interpretación reológica y cinemática. Geogaceta, 61: 75-78. (http://www.sociedadgeologica.es/archivos/geogacetas/geo61/geo61_19p75_78.pdf)

Casas-Sainz, A.M., Gil-Imaz, A., Simón, J.L., Izquierdo Llavall, Aldega, E.L., Román-Berdiel, T., Osácar, M.C., Pueyo-Anchuela, O., Ansón, M., García-Lasanta, C., Corrado, S., Invernizzi, C., Caricchi, C. (2018): Strain indicators and magnetic fabric in intraplate fault zones: Case study of Daroca thrust, Iberian Chain, Spain. Tectonophysics, 730: 29-47 (10.1016/j.tecto.2018.02.013) (https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/78325/files/texto_completo.pdf

Gutierrez, F, Carbonela, D., Sevil, J., Moreno, D., Linares, R, Comas, X., Zarroca, M., Roqué,C., McCalpin, J.P. (2020): Neotectonics and late Holocene paleoseismic evidence in the Plio-Quaternary Daroca Half-graben, Iberian Chain, NE Spain. Implications for fault sorce characterization. Journal of Structural Geology, 131: 1-17 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2019.103933)

by Ferran Claudin & Kord Ernstson (March 2020)

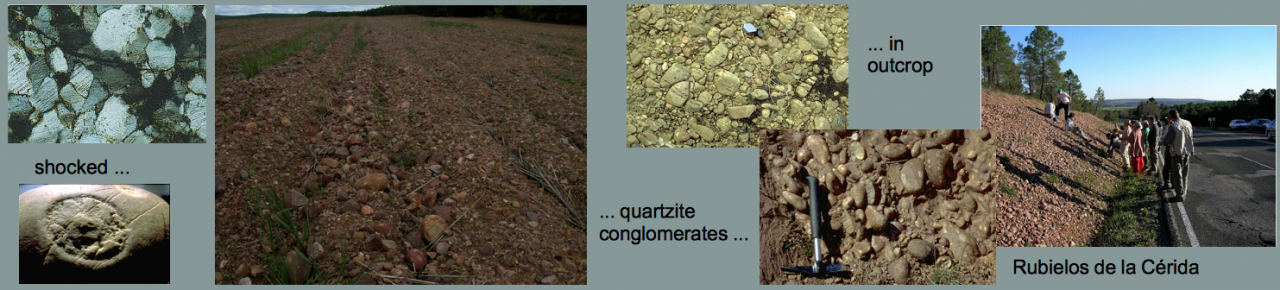

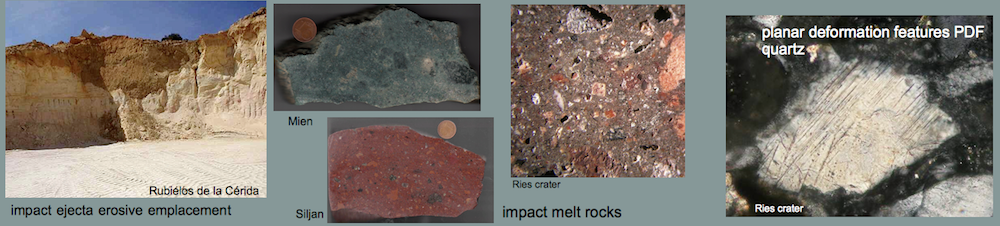

The town of Daroca in the Spanish Province of Zaragoza hides a peculiar geologic scenario – an enigma for geologists from time out of mind. Being enthroned above the town the geologic stratigraphy shows with a very sharp cut Cambrian dolomite (Ribota dolomite) over Tertiary young sediments (Fig. A). Older layers over younger ones are not uncommon in geology, and overthrust and thrust faulting are related processes. But Daroca is different. The Cambrian plate is kilometer-sized and fragmented into larger blocks, and a Tertiary 180° overtrust can reasonably be excluded. Early geologists confronted with the situation in sheer desperation thought of a preexisting Cambrian autochthonous plate and a vast undercutting by the Tertiary. Today this explanation is left out of consideration and simple thrust faulting is being favored. But the case is all but simple. There is no root zone and not any relief from where the giant plate could have started to override the Tertiary around Daroca. Nevertheless, the thrust kinematics are developed further by geologists (e.g., Capote et al. 2002), and tens of kilometers long faults are drawn within models of syn-tectonic sedimentation (Casas et al. 2000; Fig. 3).

Fig. A. The prominent Daroca exposure.

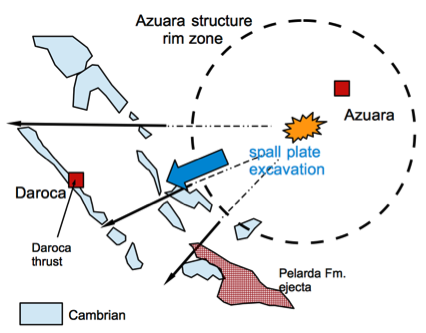

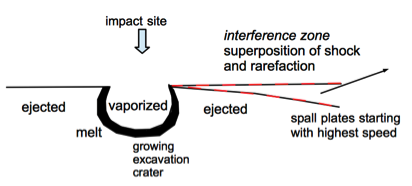

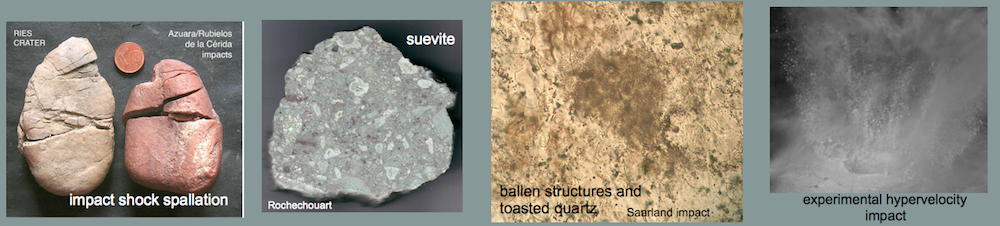

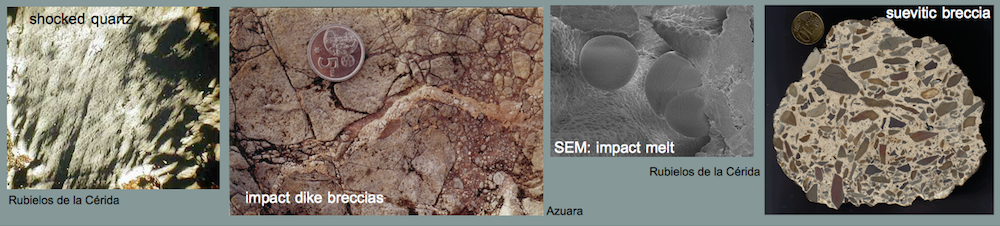

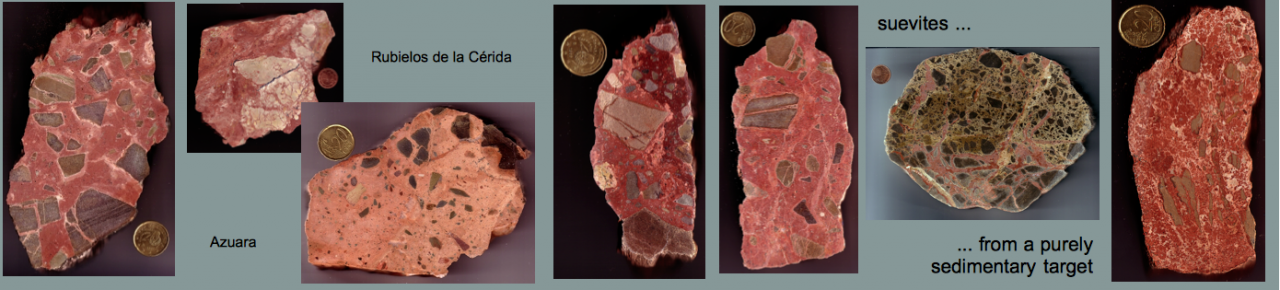

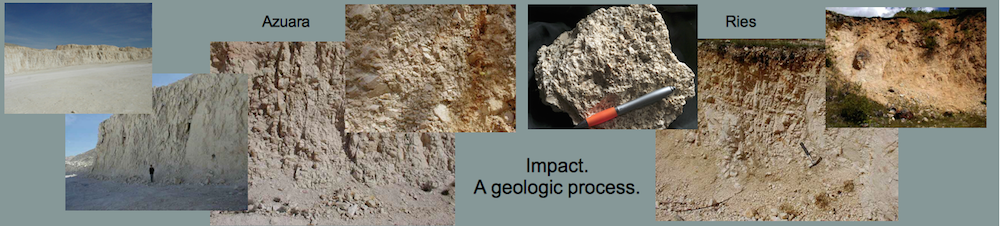

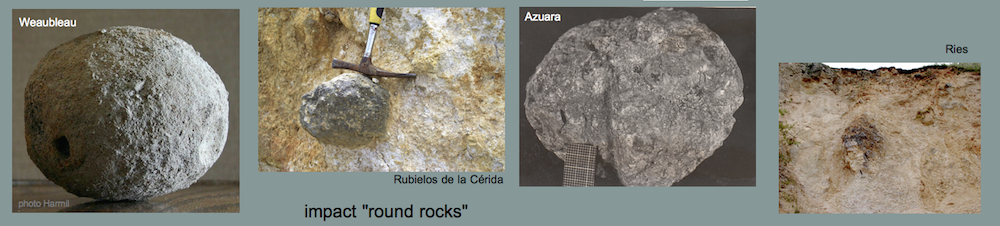

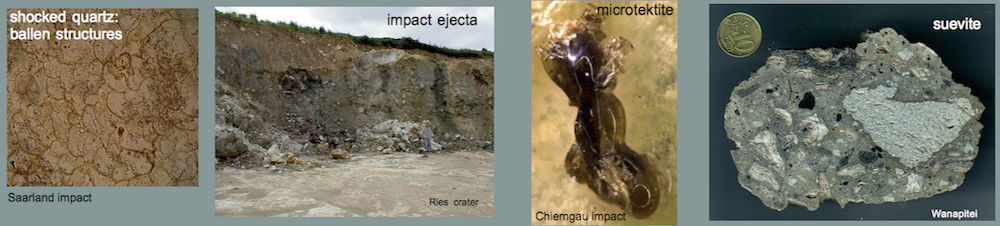

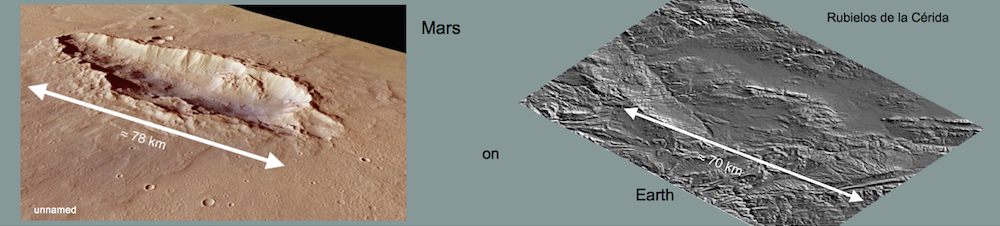

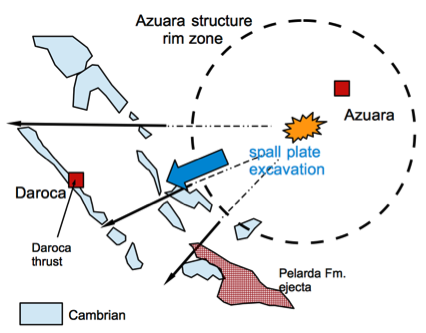

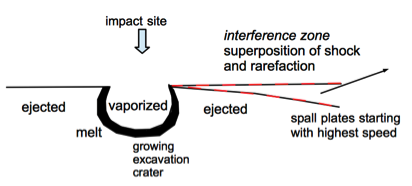

In 2012 we published an extended article (Claudin and Ernstson 2012) under the title “Azuara impact structure: The Daroca thrust geologic enigma – solved? A Ries impact structure analog“.. which proposes a new and in our opinion reasonable model of formation and a physically plausible solution of the enigma. To cut the story short, the Daroca thrust originated in the meanwhile generally established Azuara impact event, when according to the spall plate model of Melosh (1989) the Daroca Ribota dolomite plate started from the developing excavation crater and the near-surface interference zone with extreme velocity (Fig. B), supported by enormous volumes of rock melt, water and gases (water vapor and carbon dioxide from the shocked target) as a kind of hovercraft. This is no speculation but has much earlier been discussed for the so-called role-and-glide mode in the excavation process of the Ries impact crater (Germany). In our paper on the Daroca thrust we write about the affinity of both events and point to Ries giant megablocks having been excavated and transported over enormous distances.

In the case of the Daroca thrust this impressive way of transport can so nicely and conclusively be observed on the geological general map 1 : 200 000, sheet Daroca, which we show in simplified manner below (Fig. B) and in a copy of the geological map in Fig. 11 of the Spanish complete version).

Fig. B. The impact cratering model for the Daroca thrust – no intraplate fault zone (see text).

We do not know with certainty whether the authors of the three papers have read our paper and whether they have understood the herein presented simple explanation, but strangely enough since the publication of our paper on the Daroca thrust with the close relation to the Azuara impact structure, practically “overnight” a series of publications has appeared to demonstrate that the Daroca thrust has a normal tectonic fault origin, after not any geologist from Spain or elsewhere had paid attention to the enigma for decades (apart from the Casas et al. (2000) and Capote et al. (2002) papers, only seeing a tectonic fault despite all non-tectonic field evidence).

Of course, science thrives on controversy on certain topics and especially on new discoveries and models, but one principle is that the different views should be on a scientific level and that both views should be carefully discussed and balanced.

In all three papers we miss the observance of this basic scientific constitution. Not a single word is used to mention the Daroca article and the Azuara impact structure in general, and not a single one of the abundant publications on one of the most spectacular geological scenarios in Spain is found in their works. Today the Internet is a common medium and broadly used to get information about serious scientific publications (ResearchGate e.g.), and on preparing their papers a few clicks by the authors of the three papers had of course opened a host of literature about the Azuara impact event and the Daroca thrust.

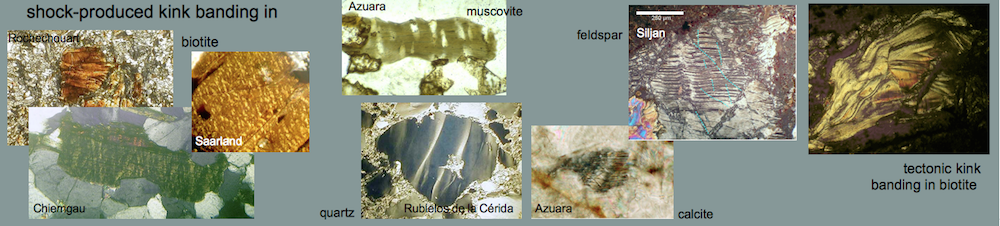

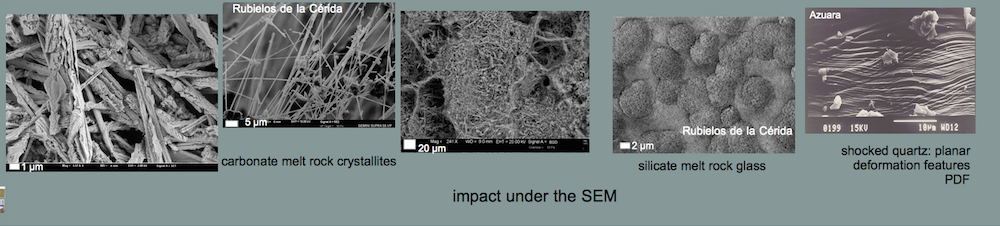

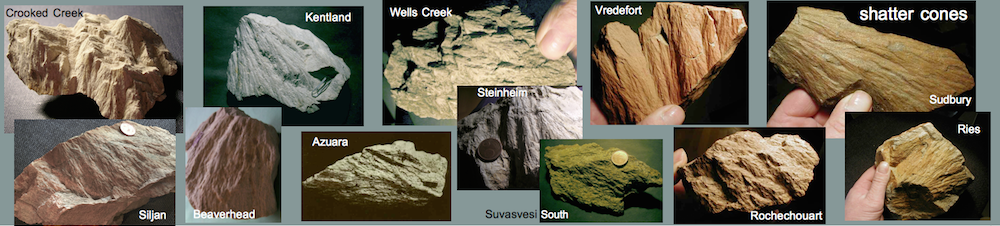

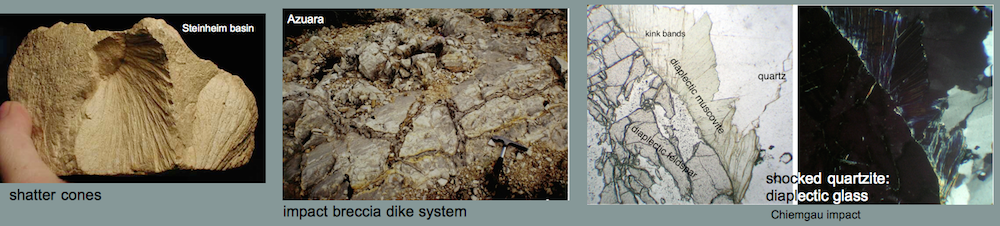

In principle our Comment article could therefore end here. But we do not want to make the same omission ignoring the papers under discussion here. In the main part of our Comment paper following below, F. Claudin has compiled an exhaustive analysis of the three Daroca “tectonic” papers confronting their in many respects rather questionable claims with standard geologic literature and with the impressive meteorite impact-related features, once more described here point by point with a host of figures that do not exist for the authors.

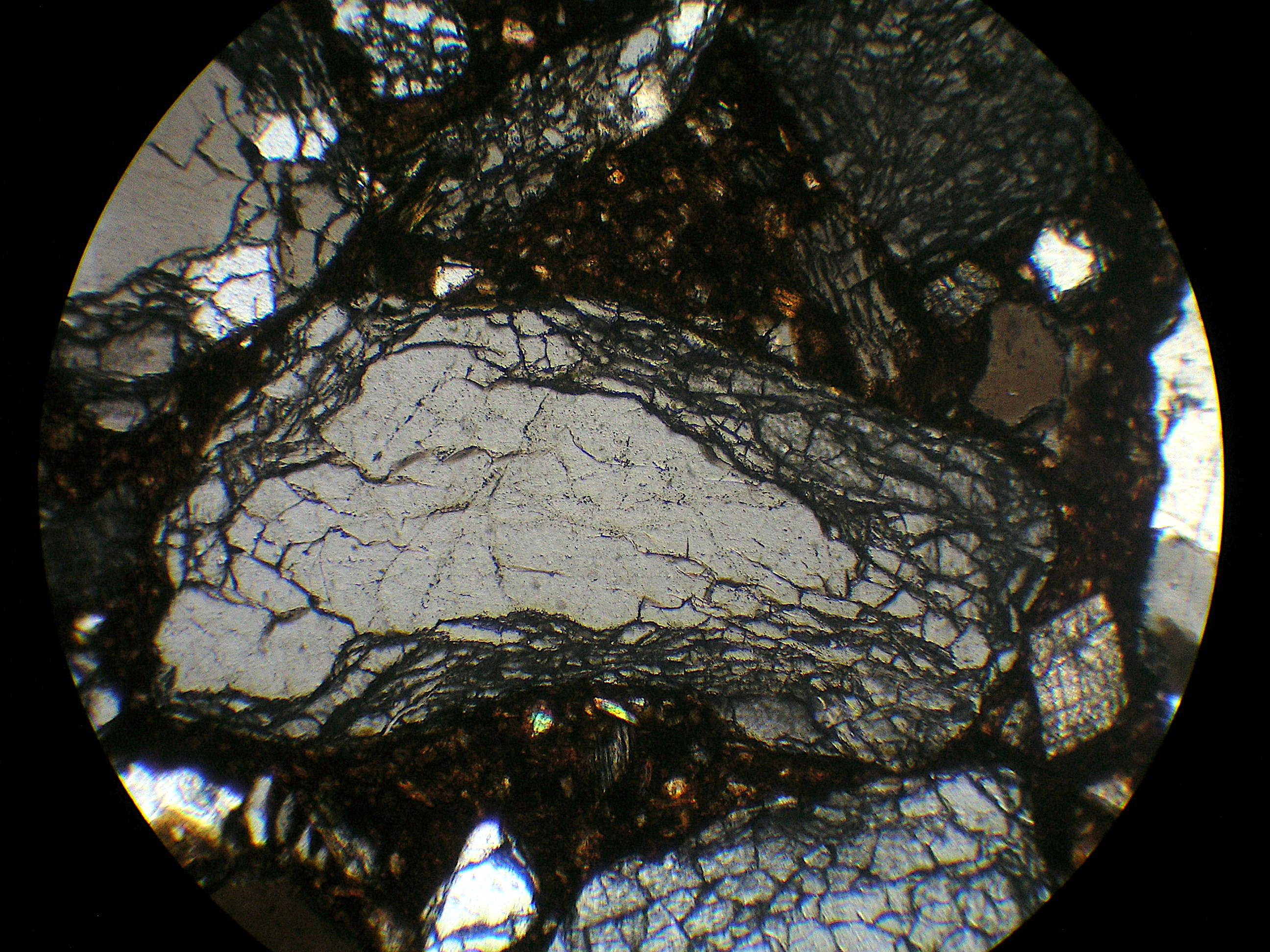

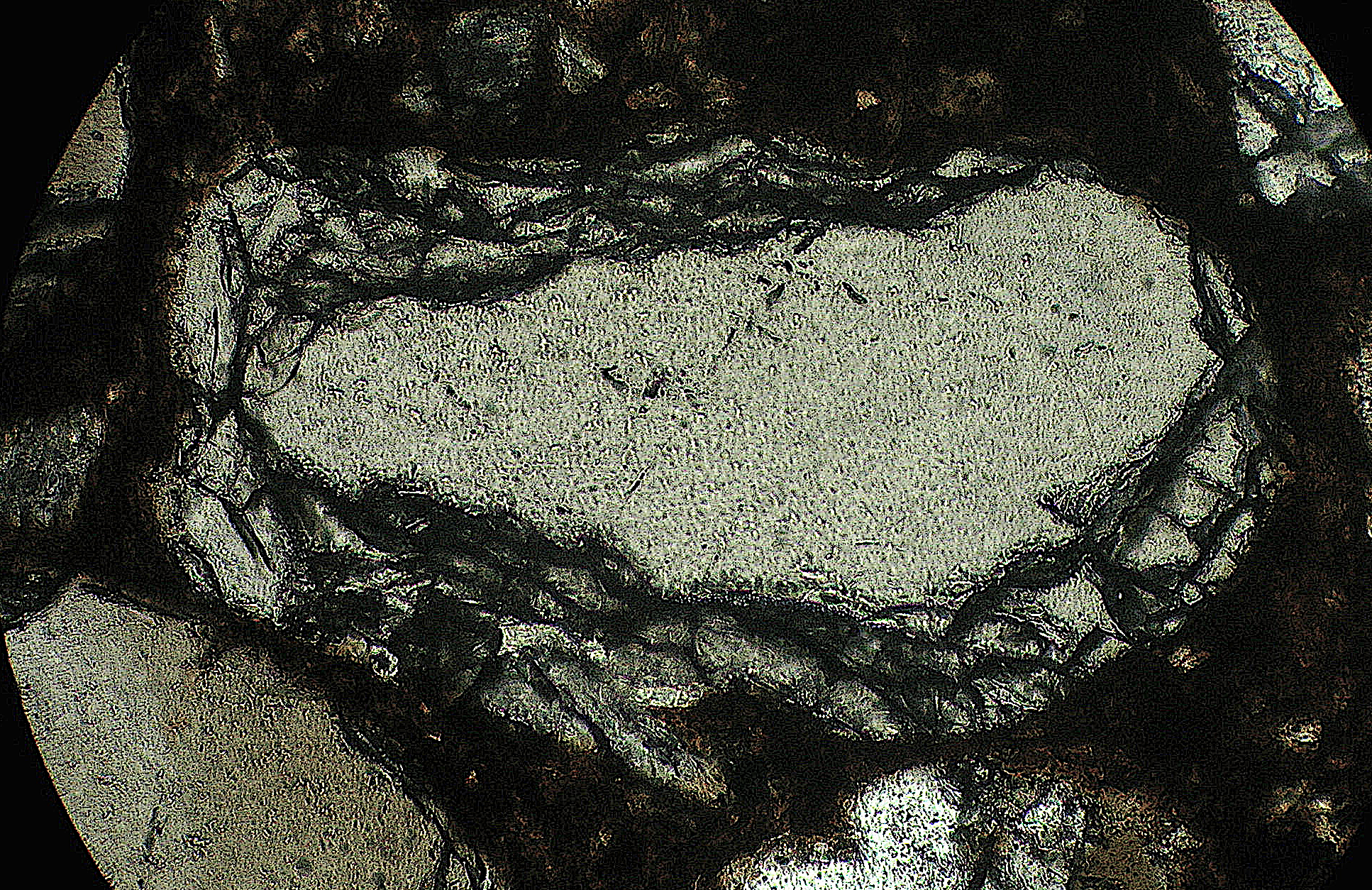

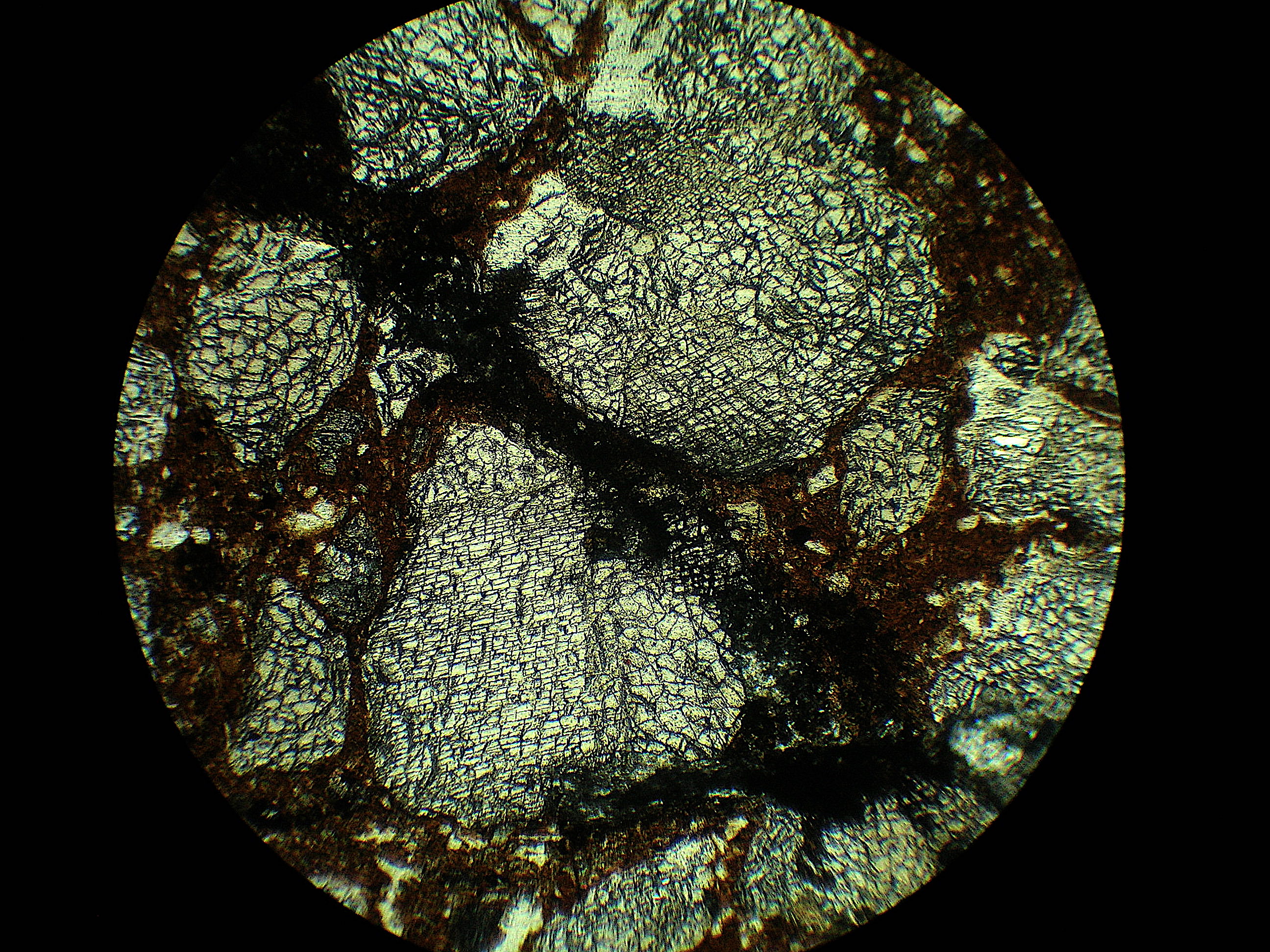

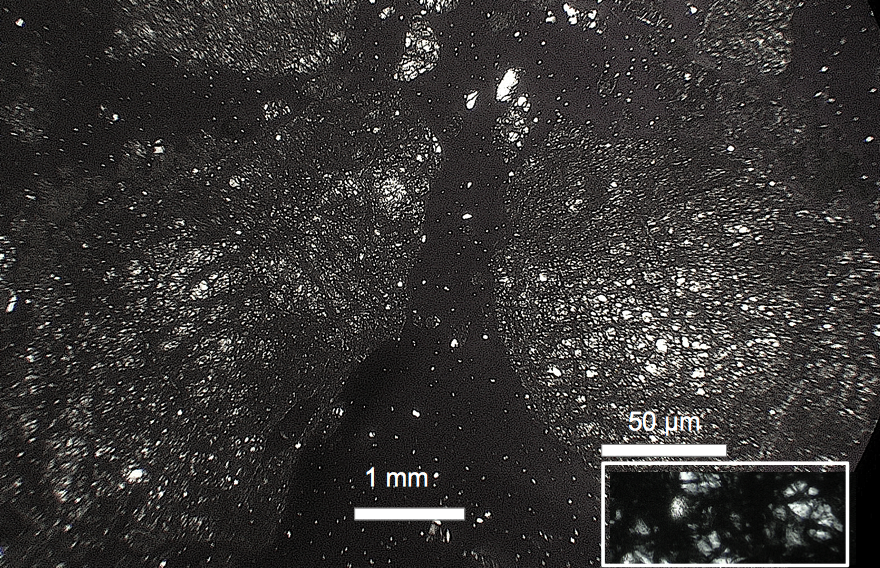

Exemplarily, one point of importance is addressed already here, the Casas-Sainz et. al. paper about magnetic fabric from AMS (anisotropy of magnetic susceptibility) and strain indicators. From the text we learn that magnetic AMS analyses were performed at 6 sites, but only a single one (no.16) is located in Daroca at the thrust exposure (their Fig. 2A). Since the site is navigated at fractures of a second, we have to proceed from a spot analysis (their Table. 1), and the rock for 12 specimen measurements is described as a fault microbreccia (their Table 3). The rest of the 5 AMS sites is located roughly 1 km southeast of Daroca (their Fig. 2A).

We imagine: For the Daroca thrust as described in very detail in our paper (Claudin & Ernstson 2012), a spot few meters sized at best served for an AMS analysis of a microbreccia (we assume of Ribota dolomite) for which it is obviously not known when it acquired the brecciation and a resulting AMS texture.

Considering now the Daroca thrust impact model of an enormously dislocated spall plate, which Casas-Sainz et al. completely ignore, what will a point AMS tell us about old in situ tectonics and intraplate fault zones? Nothing. The Daroca plate may have transported magnetic textures from its original place more than 10 km to the east, intense brecciation and other deformation (which can be seen in Daroca outcrops) in the excavation, ejection, transport and emplacement processes should have produced a completely new texture, not to forget possible strong temperature overprint in the impact cratering process.

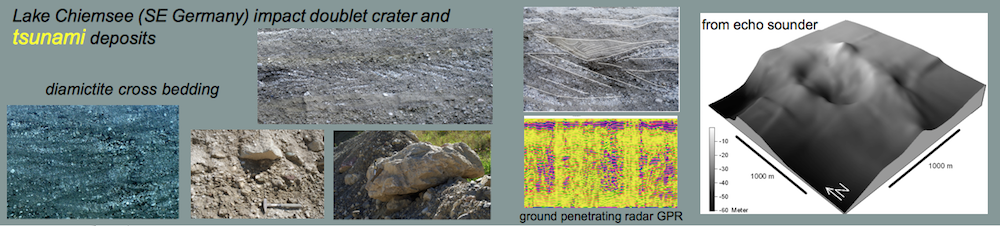

The same holds true for the five other sites of AMS analyses. Since the aim and outcome of the paper is basically the AMS of the thrust zone, more than a little methodological insight into the authors’ working cannot be recognized. The paper of Gutierrez et al. (2020) does not differ in any way in this respect. Their ground penetrating radar (GPR) and resistivity measurements at Daroca are good to look at, but for the topic under discussion they are absolutely meaningless. The idea arises that the visual impression of scientific evidence for the so-called Daroca Half-graben is to be created by the pure application of a few geophysical measurements on a very small area.

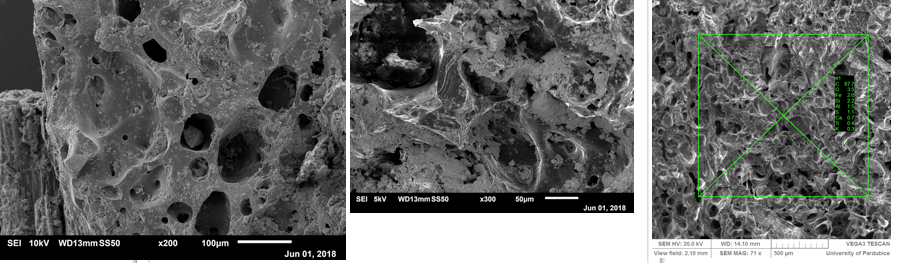

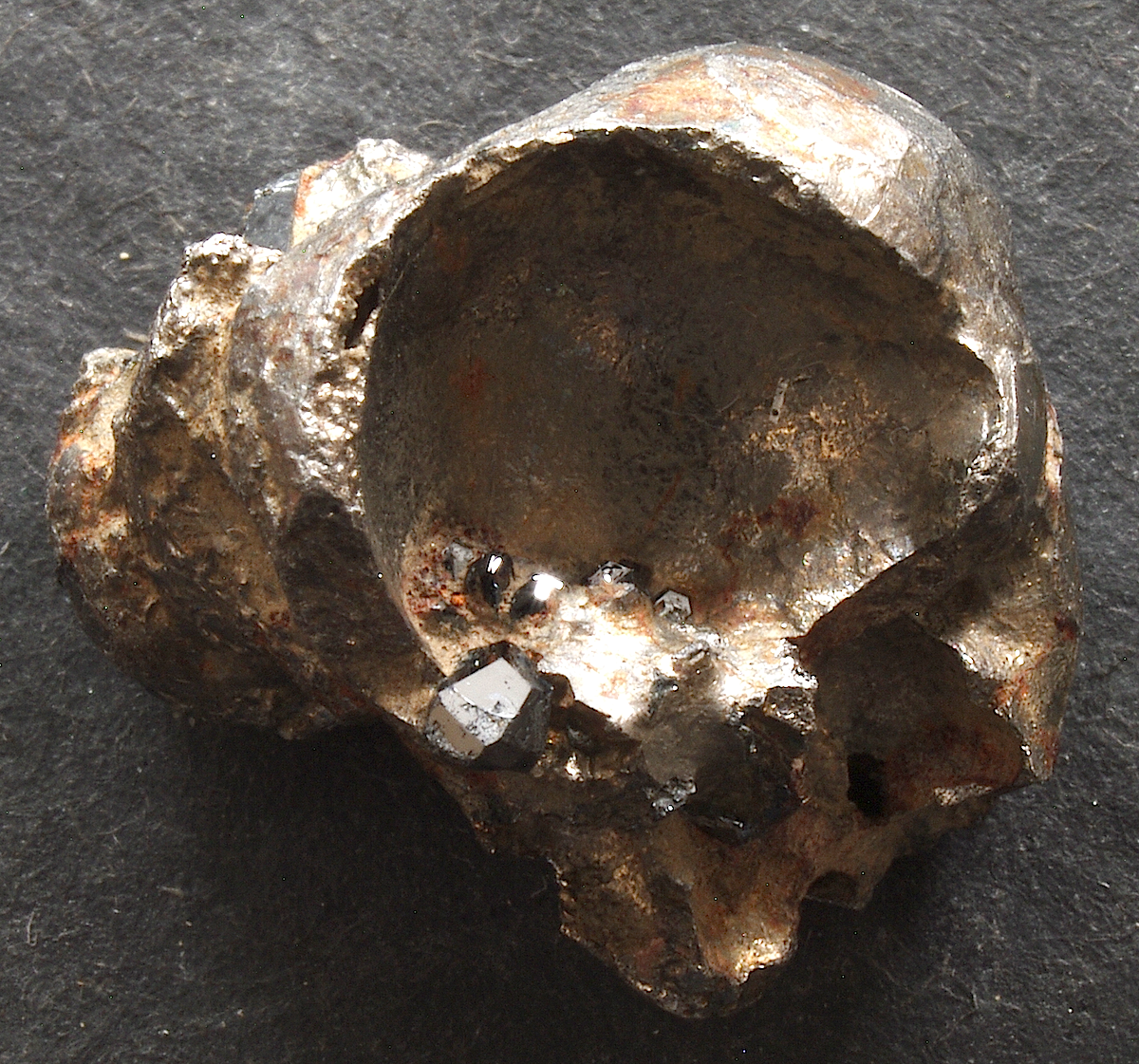

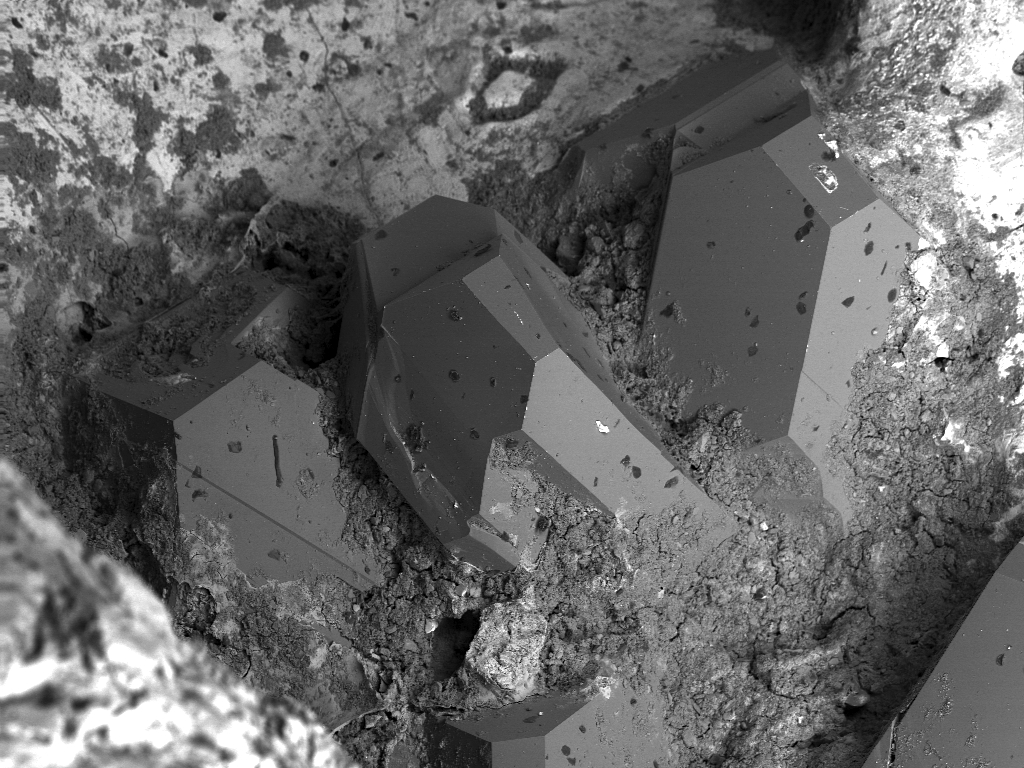

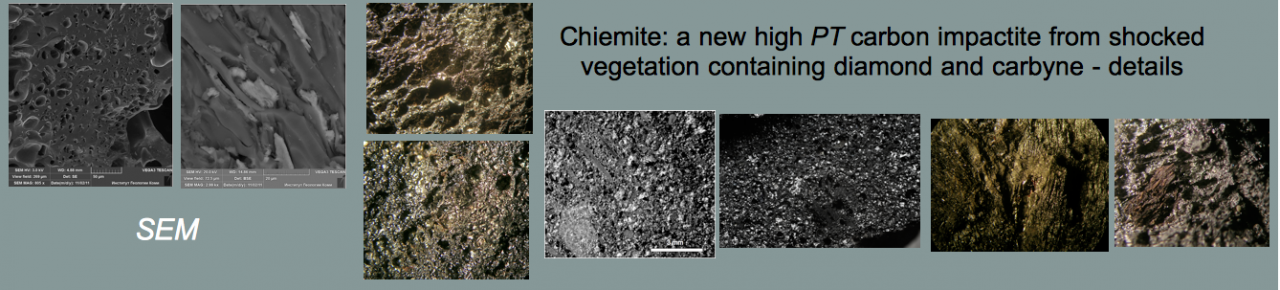

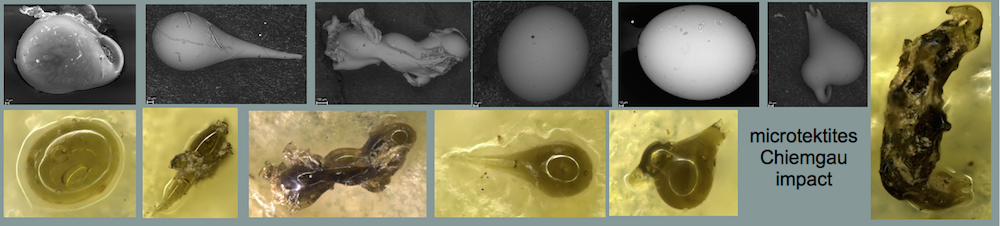

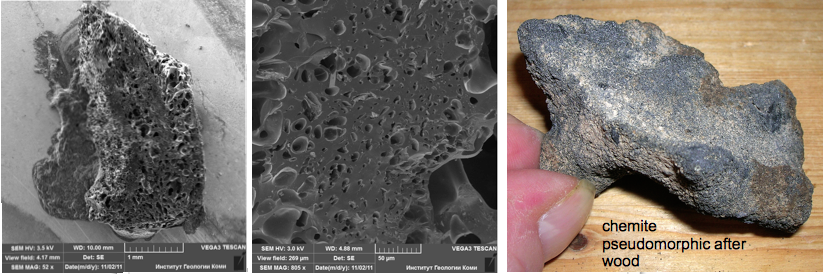

Chiemite, which is described in international, renowned peer-reviewed publication organs as high pressure/high temperature impactite with the contents of diamond and carbines (T = 2500 – 4000 K, P = several GPa), is of terrestrial origin and has originated from a spontaneous shock coalification/carbonization of the vegetation (wood, peat) of the Chiemgau impact area. The published methods of the chiemite investigation were: optical and atomic force microscopy, X‐ray fluorescence spectroscopy, scanning and transmission electron microscopy, high‐resolution Raman spectroscopy, X‐ray diffraction and differential thermal analysis, as well as by δ13C and 14C radiocarbon isotopic data analysis.

Chiemite, which is described in international, renowned peer-reviewed publication organs as high pressure/high temperature impactite with the contents of diamond and carbines (T = 2500 – 4000 K, P = several GPa), is of terrestrial origin and has originated from a spontaneous shock coalification/carbonization of the vegetation (wood, peat) of the Chiemgau impact area. The published methods of the chiemite investigation were: optical and atomic force microscopy, X‐ray fluorescence spectroscopy, scanning and transmission electron microscopy, high‐resolution Raman spectroscopy, X‐ray diffraction and differential thermal analysis, as well as by δ13C and 14C radiocarbon isotopic data analysis.