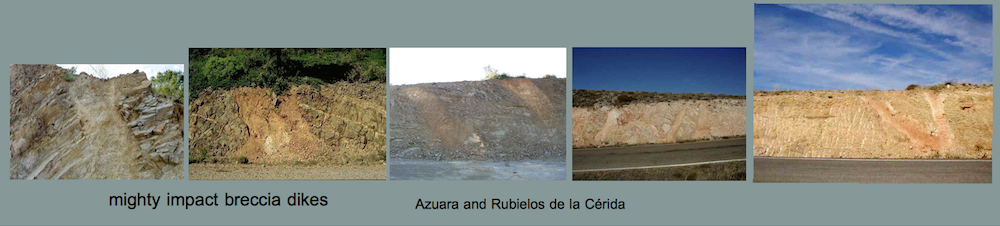

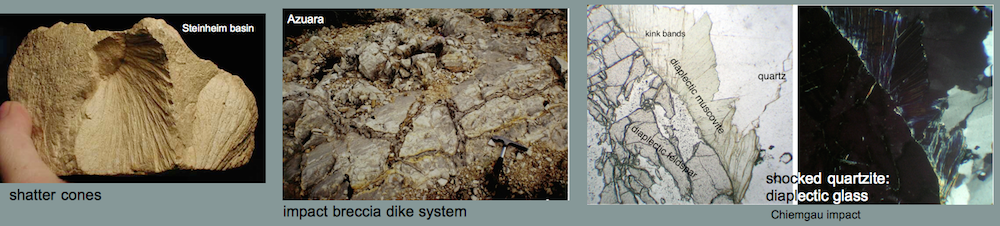

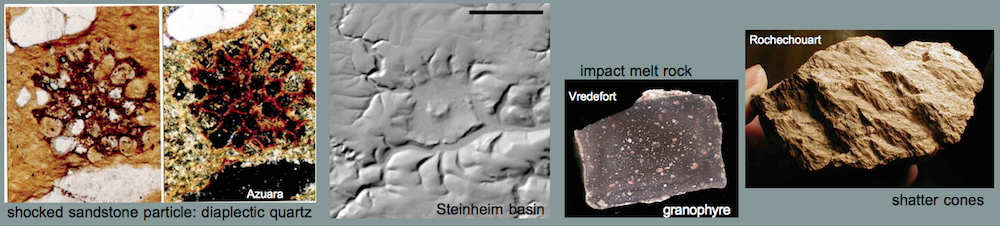

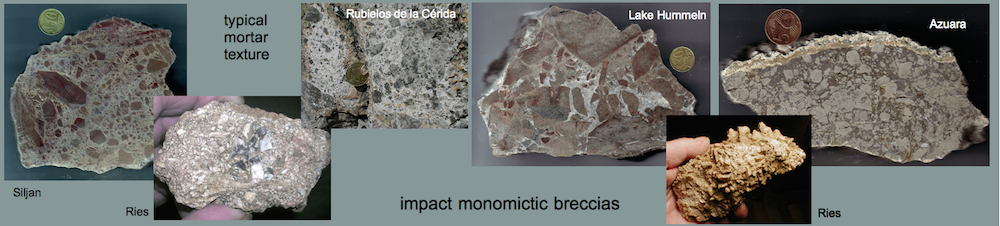

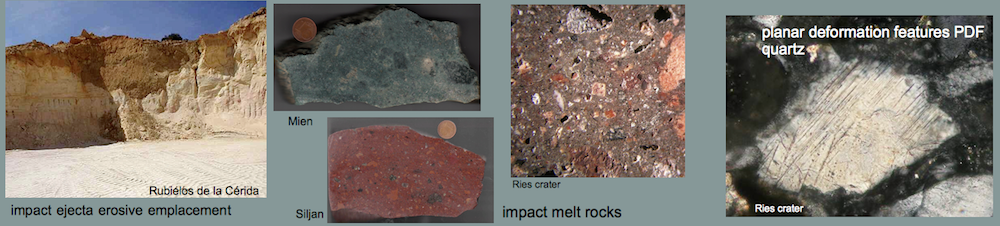

In impact structures, breccia dikes have played an important role in the understanding of the impact cratering process [see, e.g., Lambert, P. (1981): Breccia dikes: geological constraints on the formation of complex craters. – In: Multi-ring Basins (R. B. Merrill and P. H. Schultz, eds.) Proc. Lunar Planet Sci., 12A, 59-78, New York (Pergamon Press)]. They have been reported from many impact structures, and they have in detail been investigated e.g. for the Rochechouart (France) and Azuara (Spain) structures.

In the Azuara structure the abundance of impact breccia dikes and their great variability is striking [see FIEBAG, J. (1988): Contributions to the geology of the Azuara structure: Geological mapping in the area between Herrera de los Navarros and Aladrén and SE of Almonacid de la Cuba, and special investigations of the breccias and breccia dikes in the light of the impact origin of the Azuara structure. – Doctoral thesis, Univ. Würzburg, 271 pp., Würzburg (in German)].

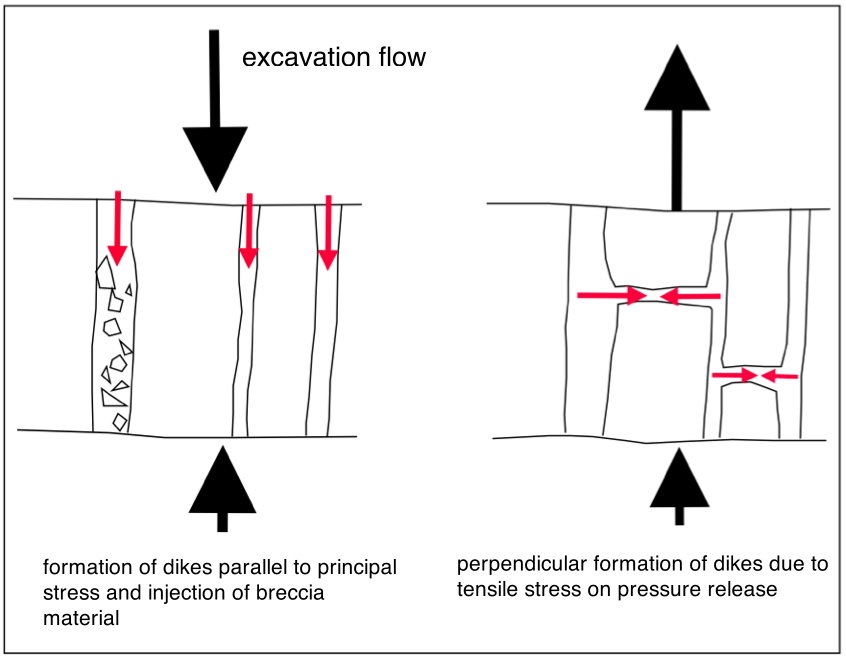

It is generally suggested that for the most part the breccia dikes are formed in the excavation stage by injection of brecciated material into the walls and the floor of the expanding excavation cavity. Later formations of breccia dikes in the modification stage incorporating earlier formed ones may lead to generations of breccia dikes.

Simple clear-cut breccia dikes

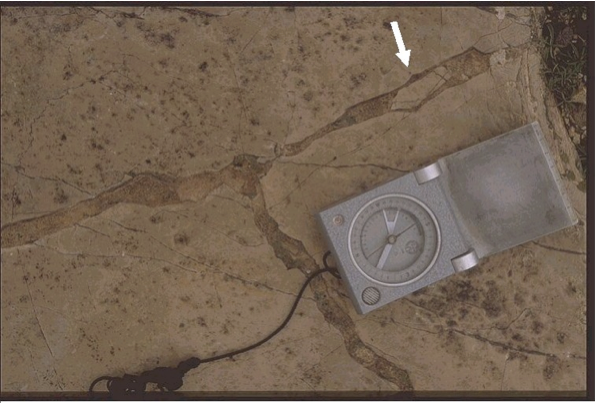

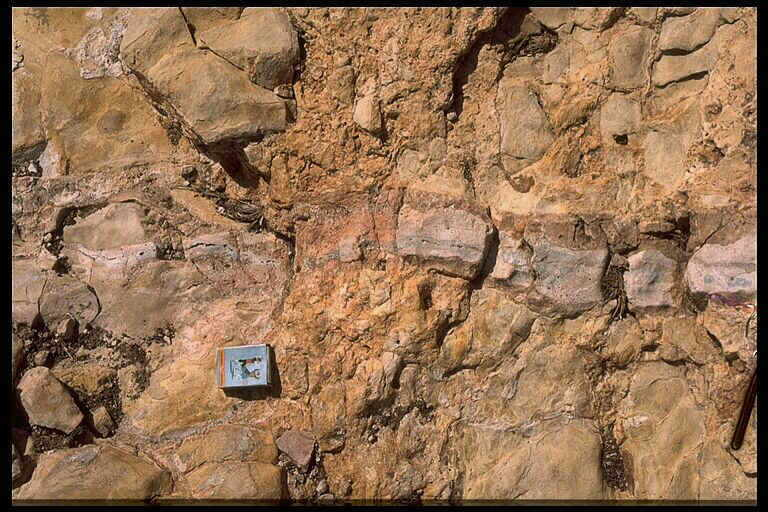

Fig 1. Breccia dikes in Malmian limestone. Note the sharp-edged splinters within the dike (arrows) incompatible with any karst phenomena. Fuendetodos; Azuara impact structure.

Fig 1. Breccia dikes in Malmian limestone. Note the sharp-edged splinters within the dike (arrows) incompatible with any karst phenomena. Fuendetodos; Azuara impact structure.

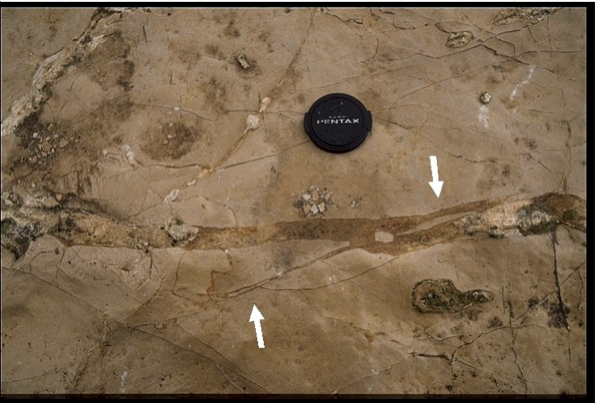

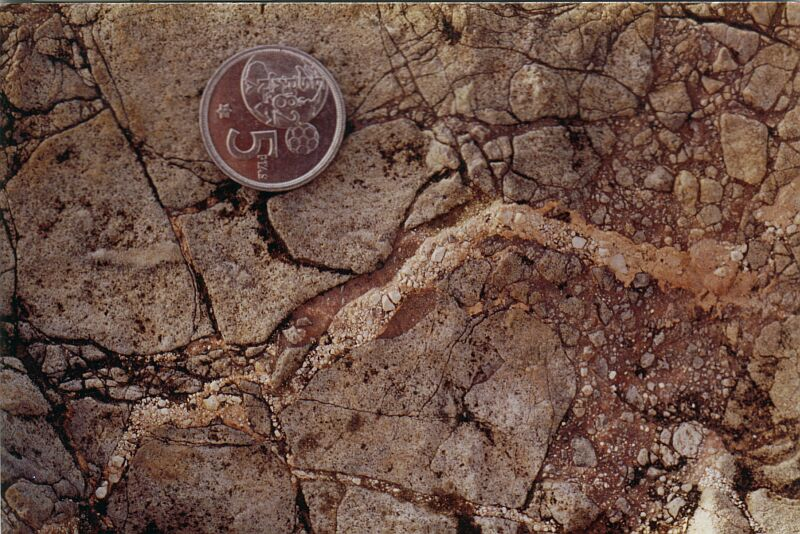

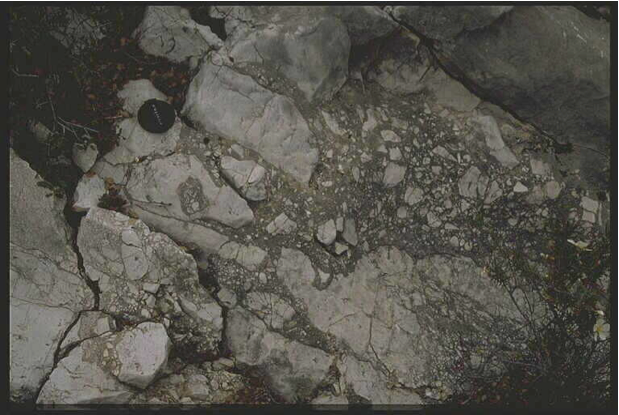

Fig. 2. Another aspect of the Fuendetodos dike. Photo-cap diameter 50 mm.

Fig. 2. Another aspect of the Fuendetodos dike. Photo-cap diameter 50 mm.

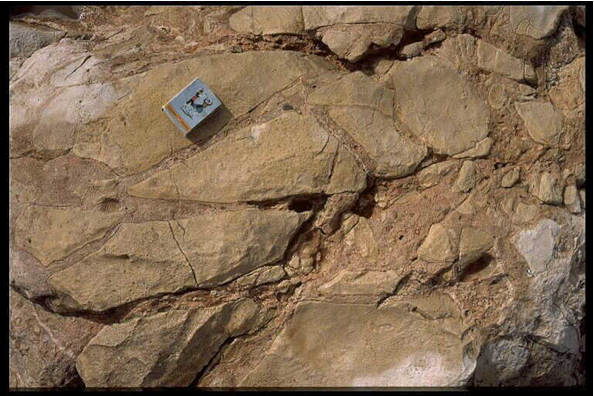

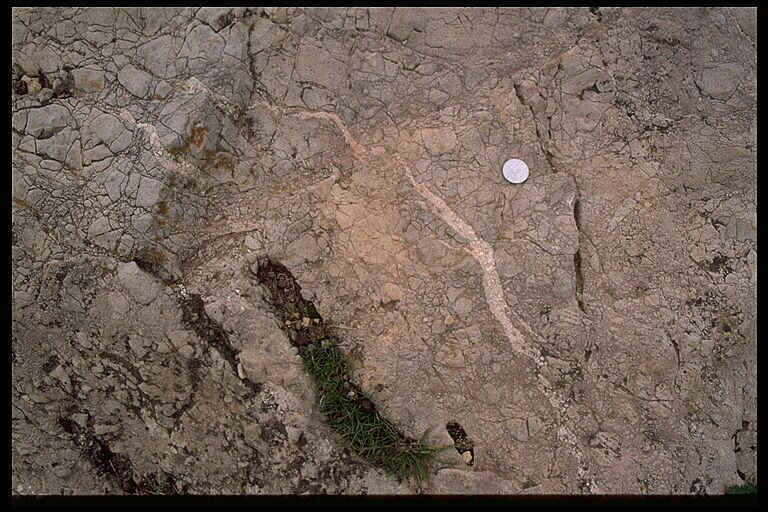

Fig. 3. Breccia dikes in Liassic limestone. Match-box length 40 mm. Blesa, Azuara impact structure

Fig. 3. Breccia dikes in Liassic limestone. Match-box length 40 mm. Blesa, Azuara impact structure

H-type impact breccia dikes

Fig. 4. Breccia dikes in Liassic limestones south of Belchite. Frequently, systems with roughly orthogonal breccia dike orientation can be observed in the Azuara (and also in the Rubielos de la Cérida) structure. We call them H-type dikes, and we suggest the systems have originated from coaction of compression and subsequent tension in the cratering process (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Breccia dikes in Liassic limestones south of Belchite. Frequently, systems with roughly orthogonal breccia dike orientation can be observed in the Azuara (and also in the Rubielos de la Cérida) structure. We call them H-type dikes, and we suggest the systems have originated from coaction of compression and subsequent tension in the cratering process (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Simple model of H-type dike formation.

Fig. 5. Simple model of H-type dike formation.

Fig. 6. System of H-type breccia dikes. Jaulín, Azuara impact structure, northern rim zone.

Fig. 6. System of H-type breccia dikes. Jaulín, Azuara impact structure, northern rim zone.

Fig. 7. H-type breccia dike system in Jurassic limestone. Fuendetodos, Azuara northern ring zone.

Fig. 8. H-type breccia dike system in Jurassic limestone. near Rudilla, Azuara southern rim zone.

Fig. 8. H-type breccia dike system in Jurassic limestone. near Rudilla, Azuara southern rim zone.

Breccia dikes-within-dikes, breccia dike generations

Breccia dike generations are a common observation in impact structures which is related with the complex excavation and modification stages in impact cratering. Breccia dikes may intersect, they may run into one another and they may cut through broader breccia zones. An example of each is shown in the images below.

Fig. 9. Crossing breccia dikes (dike generations) in Malmian limestone. The first emplaced dike (N – S trending) is cut by the younger dike showing ribbon texture probably originating from chemical interactions between dike material and the host rock. Azuara impact structure; near Ventas de Muniesa, Corral de Cámaras. Match-box length 40 mm.

Fig. 9. Crossing breccia dikes (dike generations) in Malmian limestone. The first emplaced dike (N – S trending) is cut by the younger dike showing ribbon texture probably originating from chemical interactions between dike material and the host rock. Azuara impact structure; near Ventas de Muniesa, Corral de Cámaras. Match-box length 40 mm.

Fig. 10. Breccia dike generations: The younger dike partly runs within the older one. Whitish Muschelkalk dike within Keuper dike in Carniolas host rock (also see Ernstson & Fiebag 1992). Monforte de Moyuela; coin diameter 23 mm. Dikes-within-dikes are known also from the Vredefort impact structure.

Fig. 10. Breccia dike generations: The younger dike partly runs within the older one. Whitish Muschelkalk dike within Keuper dike in Carniolas host rock (also see Ernstson & Fiebag 1992). Monforte de Moyuela; coin diameter 23 mm. Dikes-within-dikes are known also from the Vredefort impact structure.

Fig. 11. Breccia dikes cutting through brecciated (mortar texture) Muschelkalk limestone. Azuara impact structure; Monforte de Moyuela. Coin diameter 23 mm.

Fig. 11. Breccia dikes cutting through brecciated (mortar texture) Muschelkalk limestone. Azuara impact structure; Monforte de Moyuela. Coin diameter 23 mm.

Thick breccia dikes

Fig. 12. Large breccia dike composed of Mesozoic (?Keuper) and ?Lower Tertiary material cutting through Paleozoic siltstones. Near Santuario Virgen de Herrera. In earlier geologic mappings the dike was interpreted as a tectonic graben structure with 200 m throw.

Fig. 12. Large breccia dike composed of Mesozoic (?Keuper) and ?Lower Tertiary material cutting through Paleozoic siltstones. Near Santuario Virgen de Herrera. In earlier geologic mappings the dike was interpreted as a tectonic graben structure with 200 m throw.

Fig. 13. Polymictic breccia dike cutting through Malmian limestones. The dike can be traced in the field over nearly 300 m. Three dike generations can be differentiated. Many components are themselves breccias. Azuara impact structure; north of Muniesa

Fig. 14. Pair of prominent breccia dikes cutting through Cambrian siltstones; Autovía Mudéjar, Paleozoic rim zone of the Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 14. Pair of prominent breccia dikes cutting through Cambrian siltstones; Autovía Mudéjar, Paleozoic rim zone of the Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 15. Thick breccia dikes cutting through megabrecciated Jurassic limestones. Near Moyuela, Azuara impact structure. Obviously, the dikes were emplaced in a later stage (modification stage?) of impact cratering.

Fig. 15. Thick breccia dikes cutting through megabrecciated Jurassic limestones. Near Moyuela, Azuara impact structure. Obviously, the dikes were emplaced in a later stage (modification stage?) of impact cratering.

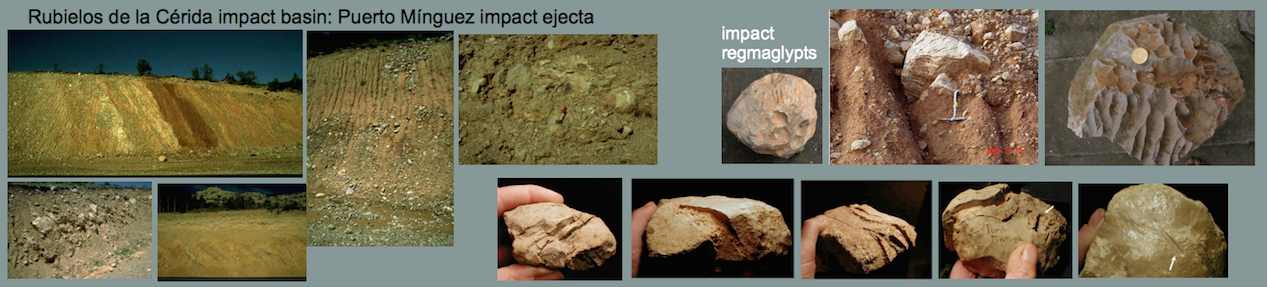

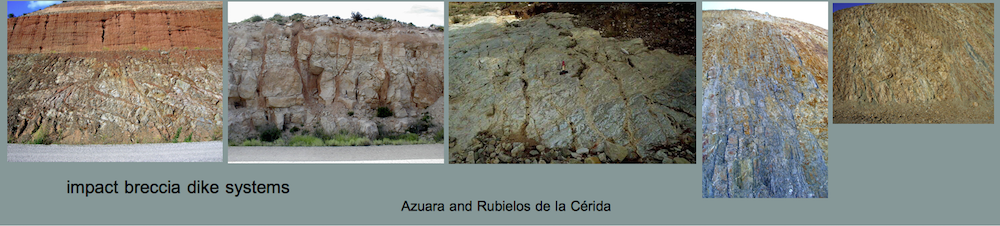

Breccia dike systems

Larger systems of branched breccia dikes are abundant in the large Spanish impact structures. Basically confused with karst structures or simply overlooked by regional geologists the injection character of the impact dikes can easily be shown in practically all cases. The interpretation as karst features becomes particularly strange in the case of breccia dikes and breccia dike systems cutting through silicate rocks.

This is especially the case with the many breccia dike systems that were exposed during the construction of the Autovía Mudéjar through the northwestern rim zone of the Azuara zone. A special chapter (to be clicked HERE) is dedicated to the respective geology and the enormous problems the constructors were surprisingly confronted with, because local and regional geologist had omitted to warn them of an unstable ground in the impact-affected region. Unfortunately (for the constructors), the geologists from Zaragoza are still ignoring the Azuara impact event.

Fig. 16. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 16. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 17. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic rocks. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 17. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic rocks. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 18. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction. The greenish dike breccia is in fact a monolithologic allochthonous chunky material.

Fig. 18. Breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction. The greenish dike breccia is in fact a monolithologic allochthonous chunky material.

Fig. 19. Broad breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 19. Broad breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 20. Closely spaced breccia dikes cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 20. Closely spaced breccia dikes cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction.

Fig. 21. System of horizontally orientated breccia dikes cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction. The emplacement of the dikes was only possible with the “help” of strong tensile forces having acted on the large block of Paleozoic siltstones. The tensile forces can be ascribed to the strong rarefaction waves following the propagating shock front.

Fig. 21. System of horizontally orientated breccia dikes cutting through Paleozoic silt stones. Bank of the Autovía Mudéjar during construction. The emplacement of the dikes was only possible with the “help” of strong tensile forces having acted on the large block of Paleozoic siltstones. The tensile forces can be ascribed to the strong rarefaction waves following the propagating shock front.

Fig. 21. Extended breccia dike system in Dogger limestones. The sharp-cut emplacement of the dikes excludes any karstification processes. – Barranco de Bocafóz, near Almonacid de la Cuba..

Fig. 21. Extended breccia dike system in Dogger limestones. The sharp-cut emplacement of the dikes excludes any karstification processes. – Barranco de Bocafóz, near Almonacid de la Cuba..

Impact breccia dikes and pockets in rocks from the Azuara impact structure

Frequently, breccia dikes in the Azuara structure merge into characteristic breccia pockets.

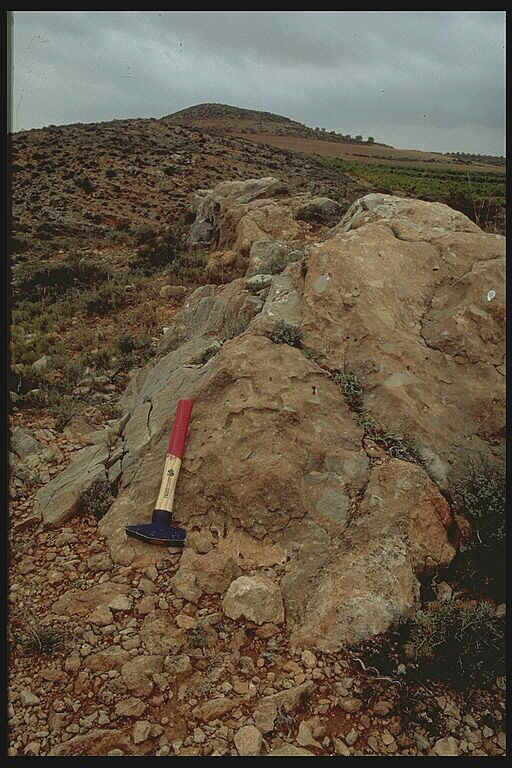

Fig. 22. System of breccia dikes and breccia pockets (dark) in light Malmian limestones. The origin of the dark material is unknown. Small quarry between Muniesa and Ventas de Muniesa. Hammer length 42 cm.

Fig. 22. System of breccia dikes and breccia pockets (dark) in light Malmian limestones. The origin of the dark material is unknown. Small quarry between Muniesa and Ventas de Muniesa. Hammer length 42 cm.

Fig. 23. Breccia dikes and breccia pockets in Liassic limestone, near Belchite.

Fig. 23. Breccia dikes and breccia pockets in Liassic limestone, near Belchite.

Fig. 24. Breccia dikes and breccia pockets in Liassic limestone, near Belchite.

Fig. 24. Breccia dikes and breccia pockets in Liassic limestone, near Belchite.

Fig. 25. Breccia pocket in Malmian limestone, near Ventas de Muniesa.

Fig. 25. Breccia pocket in Malmian limestone, near Ventas de Muniesa.

Fig. 26. Breccia pipe injected from below into Paleozoic schists. Note the ring-wall of uplifted country rock. Azuara impact structure; near Santa Cruz de Nogueras. Coin diameter 23 mm.

Fig. 26. Breccia pipe injected from below into Paleozoic schists. Note the ring-wall of uplifted country rock. Azuara impact structure; near Santa Cruz de Nogueras. Coin diameter 23 mm.

Microscopic breccia dikes

Fig. 27. Azuara impact structure, near Nogueras: Photomicrograph of microscopic breccia dike with bifurcation; plane parallel light and crossed nicols. Sandstone fragment from a shocked polymict dike breccia. Note that the thin dike cuts through several quartz grains (arrows). – The field is 2.5 mm high.

Fig. 27. Azuara impact structure, near Nogueras: Photomicrograph of microscopic breccia dike with bifurcation; plane parallel light and crossed nicols. Sandstone fragment from a shocked polymict dike breccia. Note that the thin dike cuts through several quartz grains (arrows). – The field is 2.5 mm high.

Impact dike breccias from the Azuara and the Charlevoix (Canada) impact structures

Fig 28. Impact dike breccia from the Azuara and Charlevoix impact (Fig. 29) structures. Here: Azuara polymictic dike breccia; near Santa Cruz de Nogueras. Note the grading of the components and the distinct flow texture.

Fig 28. Impact dike breccia from the Azuara and Charlevoix impact (Fig. 29) structures. Here: Azuara polymictic dike breccia; near Santa Cruz de Nogueras. Note the grading of the components and the distinct flow texture.

Fig. 29: Comparable texture in a dike breccia from the Charlevoix impact structure (sample courtesy of J. Rondot). Similar breccias have been described to occur also in the Sierra Madera impact structure (Wilshire et al. 1972).

Fig. 29: Comparable texture in a dike breccia from the Charlevoix impact structure (sample courtesy of J. Rondot). Similar breccias have been described to occur also in the Sierra Madera impact structure (Wilshire et al. 1972).