Autovía Mudéjar A-23 – the geological exposures from the 2005 campaign: road construction in an impact area

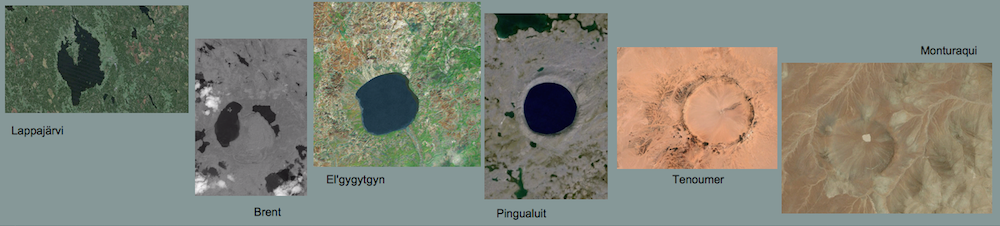

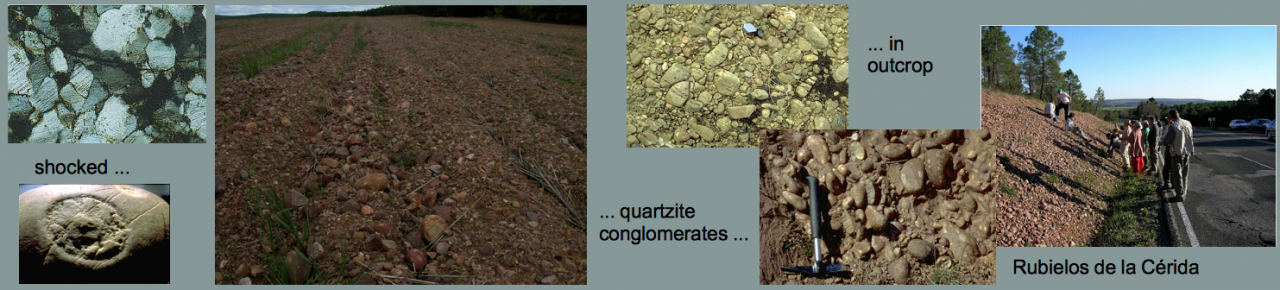

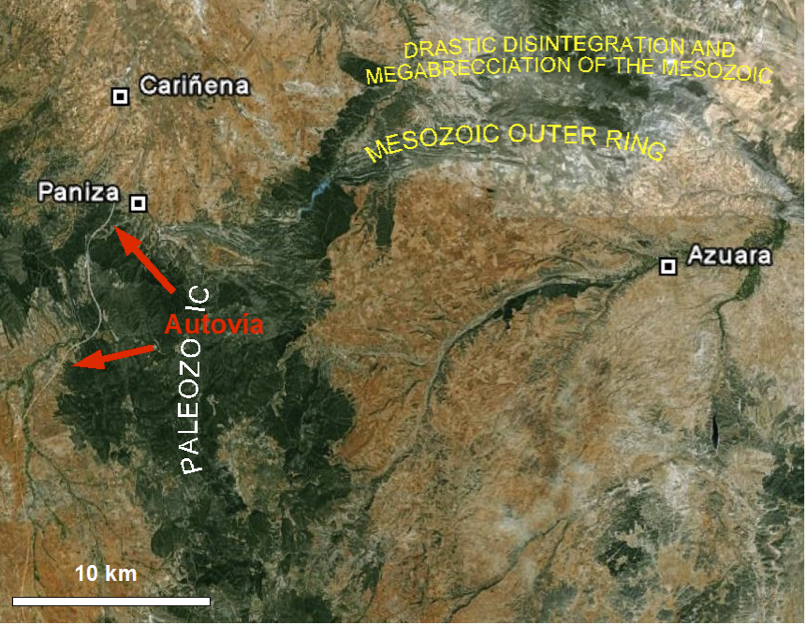

In 2005, a grand opportunity came along to study the outer rim zone of the Azuara impact structure. In the course of the construction of the Autovía Mudéjar ( http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autov%C3%ADa_Mud%C3%A9jar ) between Valencia and Zaragoza, the roadway had to cut through the Paleozoic of the mountain range of the Eastern Iberian Chain (Fig. 1). Several kilometers of bedrock nicely, not to say breathtakingly exposed in steeply dipping slopes were accessible for a time. Never before, there was such an opportunity to see and study the internal structure of the impact-affected Paleozoic rim zone in the western part of the Azuara crater. And rapidly it became evident that in the Paleozoic there is a continuation of the extensive drastic destruction of the Mesozoic rocks in the northern rim zone north of the Mesozoic outer ring structure (see Fig. 1). Unfortunately, the Autovía is meanwhile running, and the slopes are largely covered by a dense wire mesh – for reasons we are showing below. As far as we know, nobody of the geological institute of the nearby Zaragoza university has taken notice of and worked on these exceptional geological outcrops.

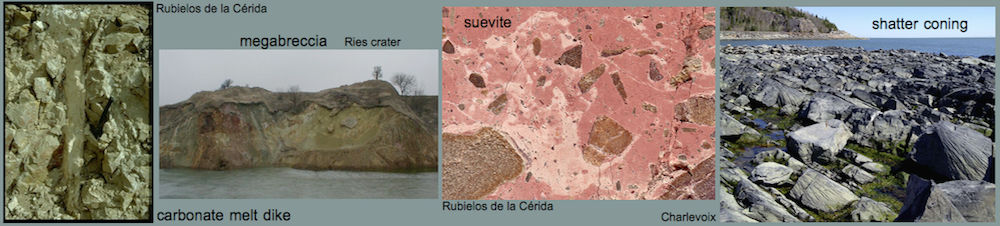

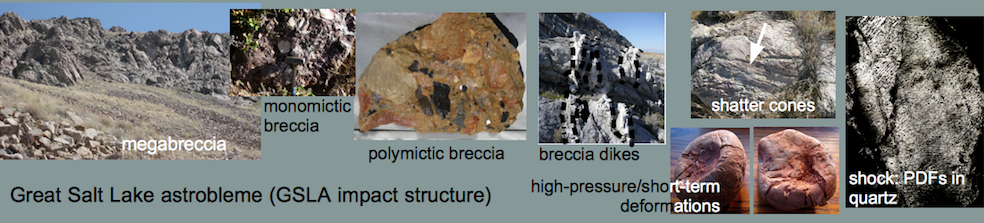

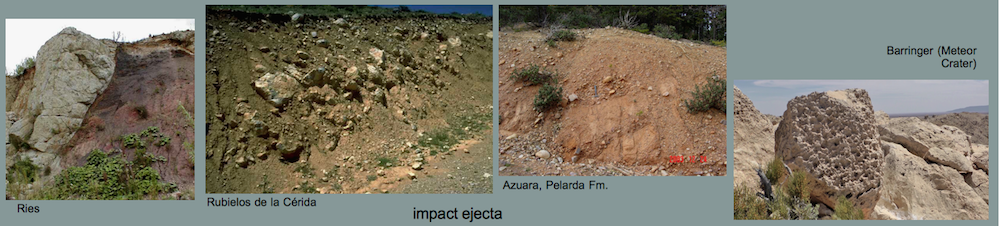

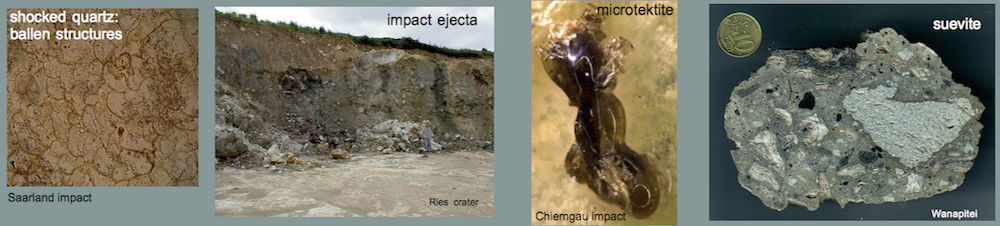

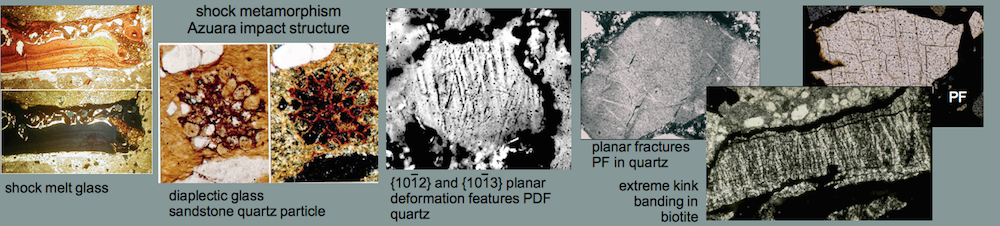

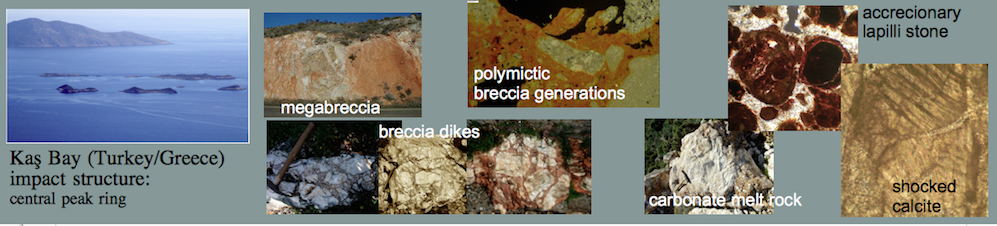

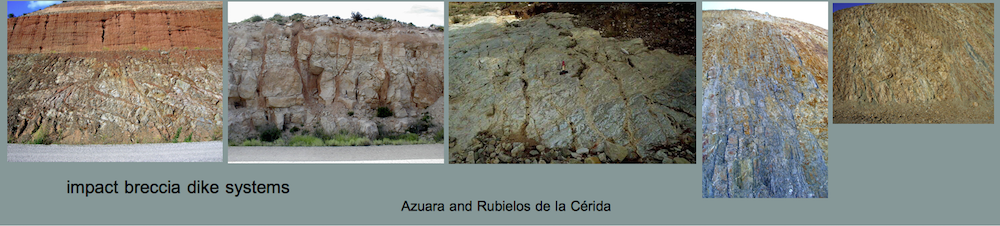

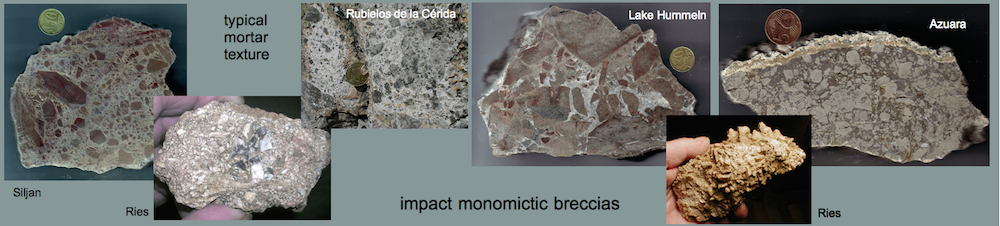

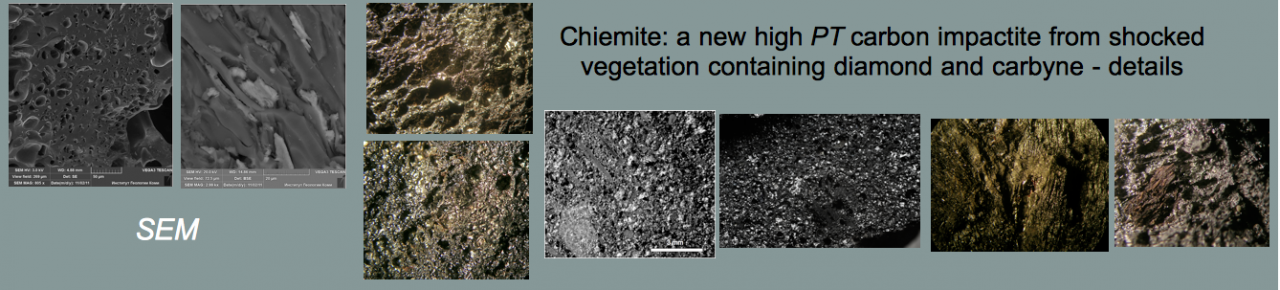

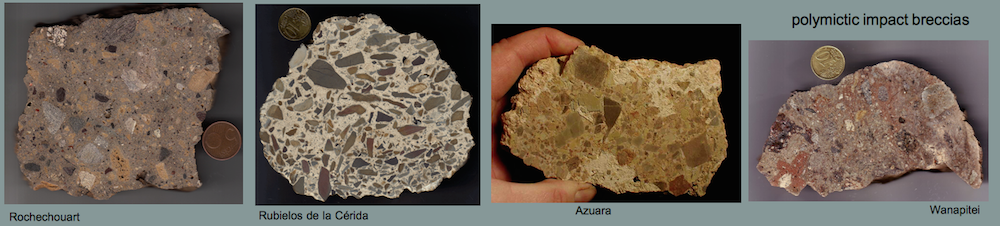

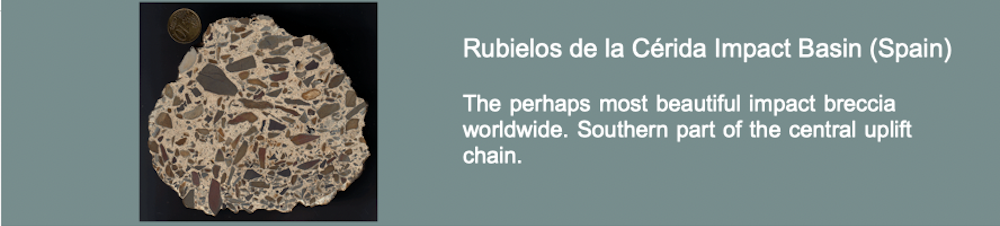

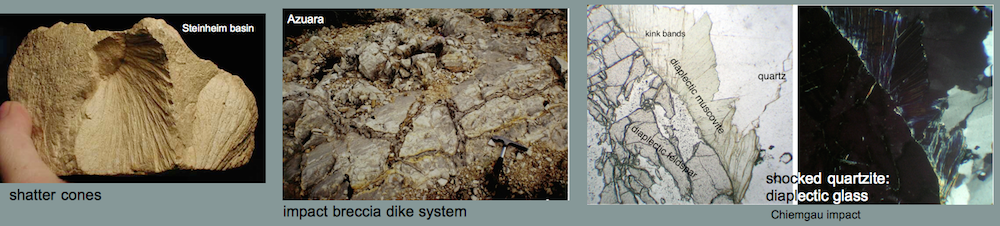

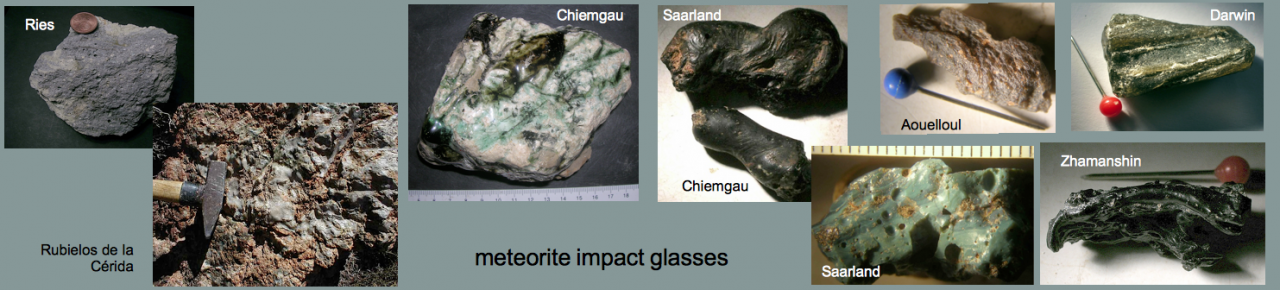

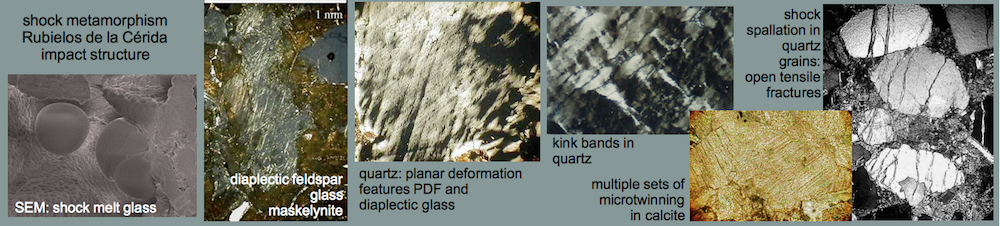

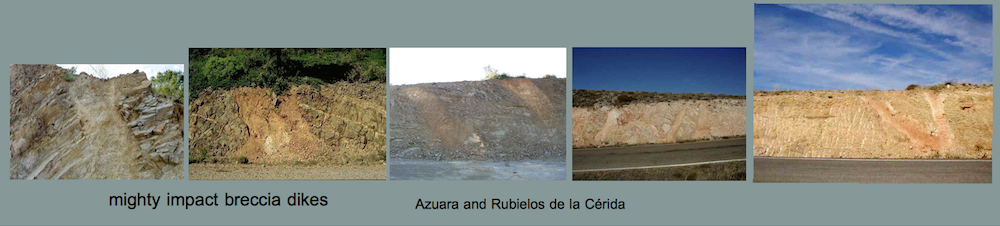

In the following we show a selection of photos typically reflecting the drastic destructions and the impact-related features, especially the abundant impact breccia dikes penetrating the Paleozoic rocks. As can convincingly be seen from the exposures, the dikes cannot be confused with tectonic fault breccias, and it is difficult to claim karstification in these silicate rocks, as might be done by opponents of an Azuara impact.

Fig. 1. Location map for the Autovía roadway south of Paniza having exposed the impact scenario in the Paleozoic rocks of the Azuara western rim zone. Google Earth.

Fig. 1. Location map for the Autovía roadway south of Paniza having exposed the impact scenario in the Paleozoic rocks of the Azuara western rim zone. Google Earth.

Fig. 2. Voluminous drastic brecciation up to megabrecciation. Figs. 3, 4 show a system of breccia dikes cutting through the complex.

Fig. 2. Voluminous drastic brecciation up to megabrecciation. Figs. 3, 4 show a system of breccia dikes cutting through the complex.

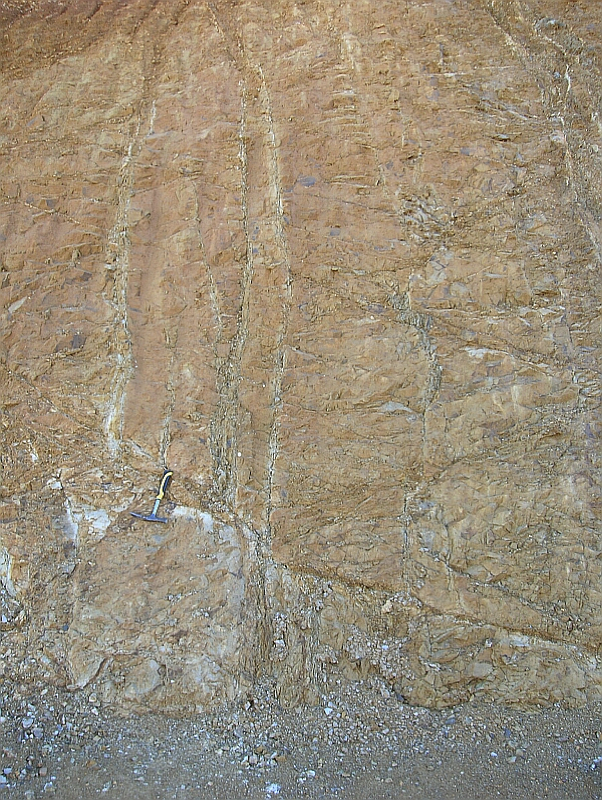

Fig. 3. Detail of the wall in Fig. 2. Close-up in Fig. 4: System of breccia dikes (H type).

Fig. 3. Detail of the wall in Fig. 2. Close-up in Fig. 4: System of breccia dikes (H type).

Fig. 4. Close-up of the breccia dike system cutting through the Paleozoic rocks. Note the typical H-type structure of the dikes very common in the Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida impact structures (see the page on the Azuara Breccia dikes ). The typical grating is incompatible with fault brecciation.

Fig. 4. Close-up of the breccia dike system cutting through the Paleozoic rocks. Note the typical H-type structure of the dikes very common in the Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida impact structures (see the page on the Azuara Breccia dikes ). The typical grating is incompatible with fault brecciation.

Fig. 5. Another aspect of the drastic destruction. Note the large internal pockets of brecciation of the hard rocks down to sand fraction (exemplified in the upper part).

Fig. 5. Another aspect of the drastic destruction. Note the large internal pockets of brecciation of the hard rocks down to sand fraction (exemplified in the upper part).

Fig. 6. Another breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic siltstones. Details in Figs. 7,8.

Fig. 6. Another breccia dike system cutting through Paleozoic siltstones. Details in Figs. 7,8.

Fig. 7. Detail of the breccia dike system in Fig. 6 again exhibiting H-type configuration.

Fig. 7. Detail of the breccia dike system in Fig. 6 again exhibiting H-type configuration.

Fig. 8. Close-up of the dikes in Fig. 7. Note that a rock of completely different facies has been injected into the host rock.

Fig. 8. Close-up of the dikes in Fig. 7. Note that a rock of completely different facies has been injected into the host rock.

Fig. 9. More breccia dikes as a system sharply cutting through the Paleozoic host rock.

Fig. 9. More breccia dikes as a system sharply cutting through the Paleozoic host rock.

Fig. 10. Close-up. Like in Fig. 8, a slaty rock as a dike penetrates a massive Paleozoic siltstone. It should be noted that in this case the dike is not composed of a breccias as such. The slaty rock is heavily fractured but has widely preserved its original texture lacking any matrix.

Fig. 10. Close-up. Like in Fig. 8, a slaty rock as a dike penetrates a massive Paleozoic siltstone. It should be noted that in this case the dike is not composed of a breccias as such. The slaty rock is heavily fractured but has widely preserved its original texture lacking any matrix.

Fig. 11. A breccia dike system fanning out down.

Fig. 11. A breccia dike system fanning out down.

Fig. 12. Breccia dike horizontally cutting through Paleozoic siltstone. Opening of the fissure und injection of the allochthonous material must have required strong tensile forces probably due to rarefaction following the shock front.

Fig. 12. Breccia dike horizontally cutting through Paleozoic siltstone. Opening of the fissure und injection of the allochthonous material must have required strong tensile forces probably due to rarefaction following the shock front.

Fig. 13. Another prominent horizontal breccia dike cutting sharply through the Paleozoic siltstones. Close-up in Fig. 14.

Fig. 13. Another prominent horizontal breccia dike cutting sharply through the Paleozoic siltstones. Close-up in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14. Close-up of the horizontal dike in Fig. 13. Note the razor sharp contact between dike material and host rock.

Fig. 14. Close-up of the horizontal dike in Fig. 13. Note the razor sharp contact between dike material and host rock.

Fig. 15. Two mighty breccia dikes cutting through heavily shattered Paleozoic rocks.

Fig. 15. Two mighty breccia dikes cutting through heavily shattered Paleozoic rocks.

Road construction in an impact area

At the beginning of our Autovía photographic field trip we mentioned that today the slopes of the road cut have largely disappeared under a dense wire mesh. Meanwhile you may have got an impression why this has been necessary, although originally the road builders obviously did not plan this step. They were, however, not aware of going to build their roadway straight through the rim zone of a very large impact structure. And since most Spanish geologists have not recognized the large impact event in their country and since especially geologists from the nearby Zaragoza university rather strive against the impact ideas, there was obviously no reason for the road builders to see things different from regions where they had constructed their roads in Paleozoic rocks without problems. So, the slopes were probably built as per usual. And as the roadway and the slopes were practically completed, the impact piped up – as can impressively be seen in the figures to follow. And now, you will understand why the road builders had to handle quite a lot of wire mesh.

Fig. 16. Land slide number 1 in the slope of the Autovía nearly completed. Impact geology and its peculiarities were obviously unknown to the road constructors.

Fig. 16. Land slide number 1 in the slope of the Autovía nearly completed. Impact geology and its peculiarities were obviously unknown to the road constructors.

Fig. 17. Land slide number 2 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 17. Land slide number 2 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 18. Land slide number 2; different view. Obviously the angle of slope chosen by the constructors was far too steep in this heavily smashed rock.

Fig. 18. Land slide number 2; different view. Obviously the angle of slope chosen by the constructors was far too steep in this heavily smashed rock.

Fig. 19. Land slide number 3 in the slope of the Autovía. Again a far too steep angle of slope.

Fig. 19. Land slide number 3 in the slope of the Autovía. Again a far too steep angle of slope.

Fig. 20. Land slide number 4 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 20. Land slide number 4 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 21. Big land slide number 5 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 21. Big land slide number 5 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 22. Land slide number 6 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 22. Land slide number 6 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 23. Land slide number 7 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 23. Land slide number 7 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 24. Land slide number 7 in closer view. Note the megablock removed from the heavily shattered rock. Again the far too steep angle of slope chosen by the constructors of the Autovía Mudéjar becomes evident.

Fig. 24. Land slide number 7 in closer view. Note the megablock removed from the heavily shattered rock. Again the far too steep angle of slope chosen by the constructors of the Autovía Mudéjar becomes evident.

Fig. 25. Land slide number 8 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 25. Land slide number 8 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 26. Land slide number 9, tilted megablocks and cavern formation.

Fig. 26. Land slide number 9, tilted megablocks and cavern formation.

Fig. 27. Land slide number 10 in the slope of the Autovía.

Fig. 27. Land slide number 10 in the slope of the Autovía.

This story of the construction of the Autovía Mudéjar through the rim zone of the big Azuara impact structure demonstrates that ignoring a really existing impact structure by geologists has not only scientific negative relevance but also quite practical (and in the end considerable financial) consequences.

As mentioned elsewhere and as for the scientific relevance we once more state that the abundant geological, tectonic and geomorphological models developed for the region between Zaragoza and Teruel are basically meaningless as long as the regional geologists are completely blocking out the Azuara impact event with the formation of the Azuara structure and the Rubielos de la Cérida elongated impact basin.